In the cabinets of prime ministers Ahmad Ghavam and Ali Soheili, I was Minister of Education and Sa’ed Maragheyi was Foreign Minister – in discussions about foreign politics and policy, Sa’ed always asked for my opinion – and he would say: “You should be the Foreign Minister.” He said this on several occasions. However, I felt it was flattery and not what he genuinely meant. But the day he became Prime Minister1328(1949), he invited me to become his Foreign Minister, and I realized that he had been serious. I thanked him but declined his offer. My reason was that I am a man of principle, serious and inflexible … traits that for a political diplomat – were not practical and could cause difficulty for his cabinet. Sa’ed did not accept my excuses and said: “You will never be a disturbance; your service was very worthy to the Ministry of Education. Now it’s time you show your capability in the Ministry of Foreign Affairs…” As I wanted to say something, he cut me off and said: “Furthermore, I told the Shah about this appointment and he approved it.” I thanked him for his goodwill and said: “If my co-operation causes any undesirable results, you will be responsible. From now can I trust that you will not oppose any changes that I might make in the Ministry of Foreign Affairs?” He said: “You can be certain.”

Important Actions taken during

my Leadership of Minister of Foreign Affairs

On August 25, 1941 a combined Soviet and British force entered Iran with the British occupying the south and the Soviets occupying Iran’s Northern provinces (Rubinstein, p. 62). Within six months Iran capitulated to the demands of the Soviets and British and formally entered into a tripartite alliance that would effectively transform Iran into a tactical and logistical partner to allied forces (Rubinstein, p. 62).

The treaty, signed in January of 1942, not only secured Iran’s allegiance to allied forces but also contained set guidelines for the withdrawal of foreign forces from Iran within six months of the conclusion of the conflict; while the British would honour their agreement by March of 1946, the Soviet decision to delay its withdrawal created more animosity between both capitals and left the Soviets firmly entrenched in Iran until May of 1946 (Rubinstein, p. 63-4).

By some accounts the Soviet withdrawal could be credited to the influence of the United Nations Security Council which had begun to intervene at Iran’s request in January of 1946, yet others suggest that the order to withdraw was given only after the USSR had achieved significant political concessions—one of which included the direct representation of the Soviet-backed Tudeh party in Prime Minister Qavam as-Saltaneh’s cabinet (Rubinstein, p. 63-4).

The day that the introductory ceremony with the foreign political representatives took place, from my brief conversation with the Russian Ambassador, I felt the horizon of our relationship looked cloudy. To brighten this horizon became part of my plan. In the relations we had with the foreigners, whether the gatherings in my honor, or other times, I discerned that the British and American Ambassadors did not want us to be too close to Russia. This feeling would not stop me from performing my national duties.

So, I told the Shah: “Do you give me permission to clear any misunderstandings there may be with Russia?” The Shah replied: “Sure, but it’s futile; they aren’t willing to co-operate, for they expect too much. You’ll only be wasting your time.” I responded: “Well, at least let me try.” I took the Shah’s silence as acceptance and that day as soon as I went to my office I , invited the Russian Ambassador (named Sadchikoff) to my office and after the customary greetings I asked him: “Why don’t you want to resolve any possible misunderstandings we have?”

With utter astonishment he said: “Are we unwilling, or are you? I have repeatedly made this request, but nobody wanted to listen.” I responded: “Possibly there may have been a misunderstanding. Regardless I am glad that we agree on the matter. Therefore, I suggest you make a specific list of the disagreements you assume we may have as well as your expectations. And we will do the same thing on our part. Then we will sit down and talk. I believe with a little bit of good-will and friendly intention we will reach an agreement.”

Several days afterwards at a ceremony, which I forget what it was about, Britain’s Chairmen of the Cultural Council said: “Sadchikoff isn’t trustworthy, meaning we wouldn’t be able to deal with him.” I realized the messengers who are everywhere had taken the information about Sadchikoff and my meeting to interested parties.

The day after the meeting with Sadchikoff, I disclosed the information to the Shah and revealed it a little later to the Prime Minister, but neither of them seemed optimistic about the result. 2 days later I told Sa’ed: “The day you invited me to work with you I notified you about my strict adherence to principle. I hope my attitude and actions haven’t and won’t hurt your cabinet.” He said: “Not at all! Don’t be concerned.” But the truth is that I was worried about him not being chosen again Prime Minister.

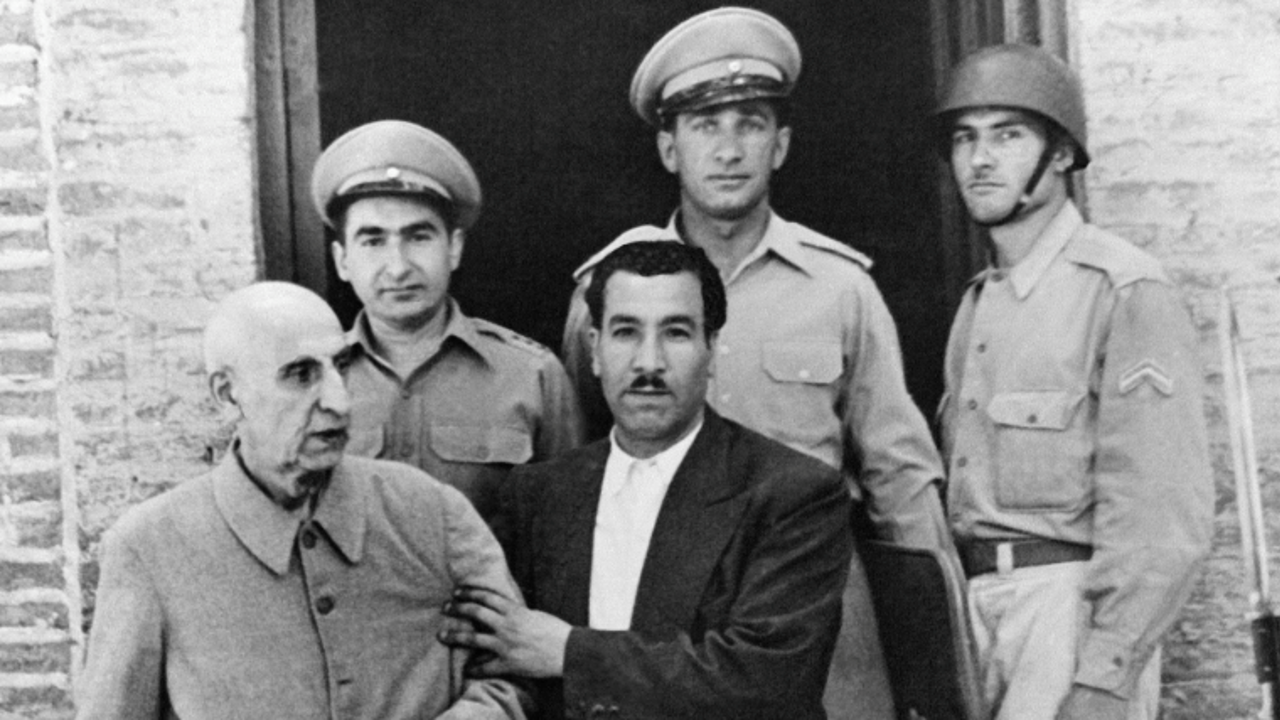

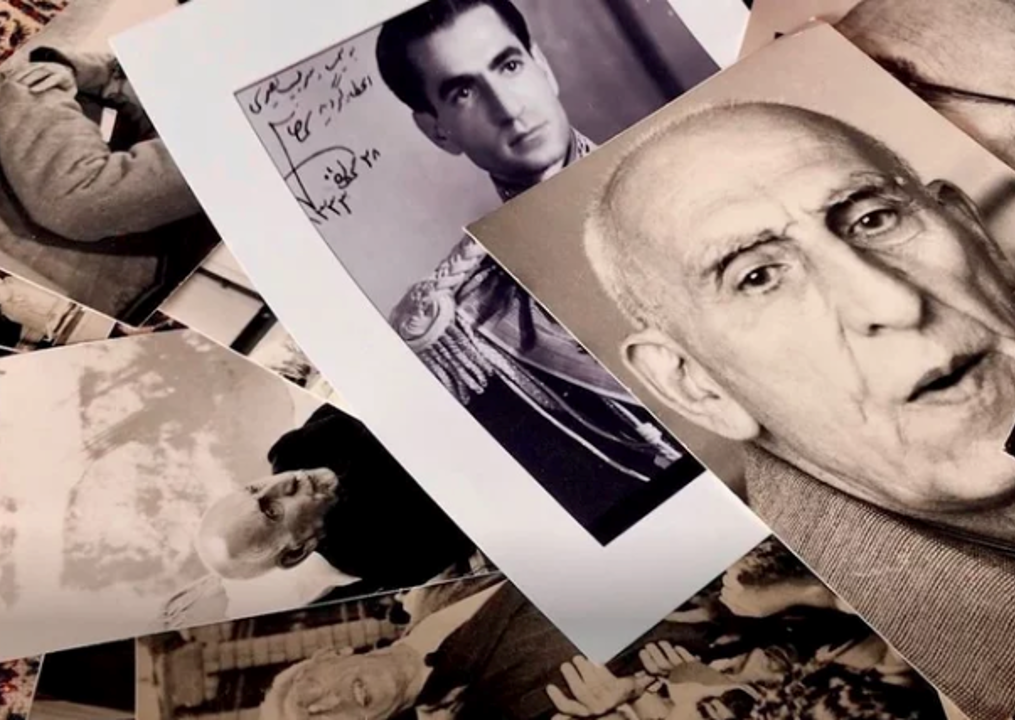

The military court after several sessions, reported in detail in newspapers, voted to give Mosaddegh 3 years in prison as its verdict. A few days later the Shah summoned me. He was standing in his office. I lowered my head out of respect and shook his outstretched hand. The first thing he said: “Now are you satisfied?”

I wasn’t surprised by this stupidity, for in my 12 years as Tehran University President, membership of 5 governmental cabinets and being in close contact with him, I knew the Shah had an excellent memory but was lacking in common sense and had an average intelligence or (IQ) of about 100 maybe even less. Proving this was his lack of insight and foresight as well as being a slave to his feelings and emotions, which, prepared the groundwork which led to the revolution.